Kasha’s Rule is named after the American molecular spectroscopist Michael Kasha and is one of the main principles in fluorescence spectroscopy. Kasha completed his PhD under famous chemist G. N. Lewis on the theory of phosphorescence emission, and together they published one of the first papers that correctly identified phosphorescence as originating from the triplet state.1,2 In 1950 Kasha published a seminal paper on the “Characterization of Electronic Transitions in Complex Molecules”3 which established how to interpret and draw conclusions from the fluorescence emission spectra of complex molecules and contained the first statement of what is now known as Kasha’s Rule.

Figure 1: Michael Kasha (1920 – 2013).1

Kasha’s Rule is best stated exactly as it was written by Kasha in 1950:2

“The emitting level of a given multiplicity is the lowest excited level of that multiplicity”

The term multiplicity refers to the spin angular momentum of the level (singlet states have a multiplicity of 1 and triplet states a multiplicity of 3). Kasha’ Rule, therefore, states that fluorescence will always originate from the vibrational ground state of the lowest excited singlet level, the S1, while phosphorescence will originate from the vibrational ground state of the lowest excited triplet level, the T1, regardless of which initial level the molecule is excited too.

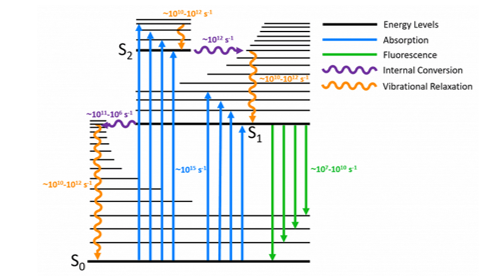

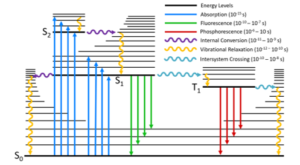

Kasha’s Rule is a consequence of the fact that in complex molecules the rate constant of internal conversion and vibrational relaxation from the higher lying electronic levels is significantly greater than the emission rate constant back to the ground state from those levels (Figure 2). The rate of internal conversion between two electronic levels is inversely proportional to the energy splitting between those levels (energy gap law). The S0 and the S1 have the largest energy splitting and the rate constant of internal conversion is comparable to that of fluorescence, and the S1 → S0 fluorescence emission is therefore observed. The higher-lying electronic excited states are closer in energy and therefore undergo faster internal conversion that outcompetes the fluorescence. As a result, when a molecule is excited to a higher excited singlet state, Sn, it will rapidly undergo internal conversion and vibrational relaxation to the vibrational ground state of the S1 before fluorescing, and only S1 → S0 fluorescence will be observed.

Kasha’s Rule is obeyed by nearly all molecules in solution, but like most scientific ‘rules’ there are exceptions. The most famous exception is azulene which has an S2 → S0 fluorescence emission. This is a consequence of the unusually high energy gap between the S2 and S1 in azulene, which results in slow internal conversion between these levels.4

Figure 2: Perrin-Jablonski diagram illustrating the origin of Kasha’s Rule.

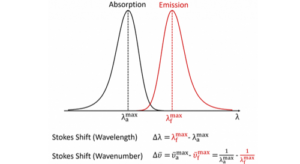

As a demonstration of Kasha’s Rule, the absorption and emission spectra of a solution of anthracene were measured using the FS5 Spectrofluorometer and are presented in Figure 3. The absorption spectra of anthracene are shown in black and have two electronic absorption bands at ~250 nm, corresponding to the S0 → S2 transition, and at 300 nm – 380 nm which is the S0 → S1 transition. The intensity of the S0 → S1 absorption has been scaled by a factor of 10 for clarity, since the S0 → S1 is a much more weakly absorbing transition than the S0 → S2.

The location of the black arrows show the excitation wavelength that was used to measure the fluorescence emission spectra displayed alongside in red. The intensity of the fluorescence emission spectra that were excited using the S0 → S1 transitions have been scaled by a factor of 10 for clarity. Figure 3 shows that the fluorescence emission always occurs at 370 nm – 450 nm (S1 → S0 transition) regardless of whether the molecule is excited to the S2 or the S1 state initially and anthracene therefore obeys Kasha’s rule.

Figure 3 also demonstrates that the fluorescence emission spectrum is independent of which vibronic band of the S0 → S1 transition is excited. This is a consequence of rapid vibrational relaxation within the S1 level itself. This results in the fluorescence emission always occurring from the vibrational ground state of the S1, and gives rise to each molecule having a unique fluorescence spectrum and is another example of Kasha’s Rule.

Figure 3: Demonstration of Kasha’s Rule in anthracene. Anthracene was dissolved in cyclohexane to give an OD of 0.1 at 376 nm, and the absorption and fluorescence emission spectra were measured using an FS5 Spectrofluorometer.

It can also be seen from Figure 3 that the intensities of the red fluorescence emission spectra are linearly proportional to the absorbance of anthracene at each excitation wavelength. In other words, the fluorescence quantum yield is independent of the excitation wavelength. In many statements of Kasha’s Rule found online the definition is expanded to include this invariance of quantum yield with wavelength; this is incorrect.

This behaviour is instead described by the lesser known Vavilov’s Rule (or Kasha-Vavilov Rule) which is named after Soviet physicist Sergey Ivanovich Vavilov (1891 – 1951) and is defined as:5

“The quantum yield of luminescence is independent of the wavelength of exciting radiation”

The majority of molecules obey both Kasha’s Rule and Vavilov’s Rule but there are exceptions. For example, in pyrene the location and shape of the fluorescence emission spectrum is independent of the excitation wavelength, but the quantum yield of the fluorescence is dependent on the excitation wavelength due to additional non-radiative recombination channels from the higher lying electronic excited states. Pyrene therefore obeys Kasha’s Rule but not Vavilov’s Rule.4

1. National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs, Michael Kasha

If you have enjoyed reading this article about Kasha’s Rule and would like to be the first to hear about future research from Edinburgh Instruments, please take a moment to join us on your preferred social media channel and sign up to our infrequent eNewsletter.

For more information on the theory of fluorescence spectroscopy, check out the frequently asked questions section on our blog.